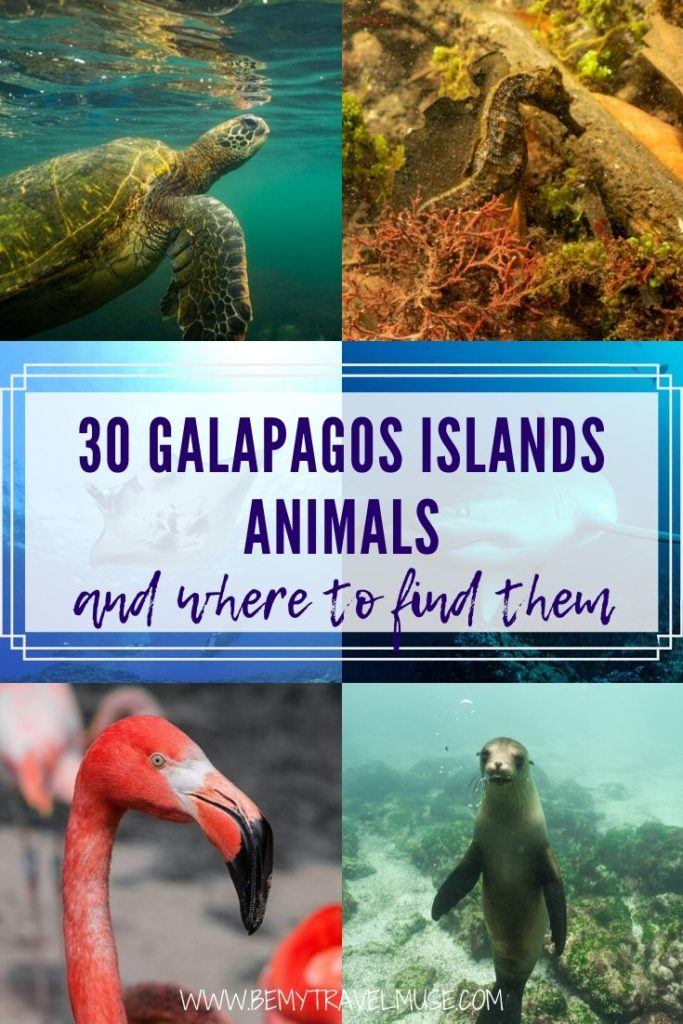

For most people, a visit to the Galapagos Islands is all about the animals. There are few places around the world where it’s possible to share such close proximity to birds, reptiles, and sea critters without them turning fearful. In the Galapagos, it’s an animal-lover’s dream come true.

That said, the Galapagos is made up of many islands and not every animal is on every island. That’s part of what makes the Galapagos so interesting – the uniquely adapted animals that only call one or a few islands home. This post has 30 of the most famous animals of the Galapagos, and where to find them:

Nazca Booby

The Nazca booby, alongside the other breeds of boobies, gets its name from the Spanish word, “bobo,” which means “foolish,” in reference to its clumsy nature. Nazca boobies are white with black tail feathers and have grey-colored feet in contrast with red-footed and blue-footed boobies. They dive for food in the waters surrounding the Galapagos Islands and reside primarily on the islands of Genovesa, Española, and San Cristobal. While they nest from August to February, they’re visible all year round. They’re also the largest and most aggressive of the boobies (but with each other, not people!).

Blue-Footed Booby

The blue-footed booby is famous for its big blue feet, which play an important role in the species’ elaborate courtship dances. Some speculate that females will choose mates with the brightest feet, as the vibrance of the blue pigmentation might convey health and gene strength. Often, a pair stays together for life! These birds are interesting for more than just their feet, though: when they look for food, they often travel in huge packs of up to 200, and when a blue-footed booby spots a fish in the water, it nose-dives straight down into the ocean at speeds up to 60 miles per hour. Blue-footed boobies can be found on Fernandina, Isabela, Pinzon, Floreana, Santa Cruz, and Española; the best time to see them is during their mating season, from June to August, though they’re visible year-round.

Red-Footed Booby

The red-footed booby is the smallest of the boobies, and it is easily recognizable by its pale blue beak and bright red feet. These guys are strong flyers and can fly for nearly a hundred miles when looking for food. During mating season, the males will try to attract females by pointing their bills directly up at the sky (a behavior aptly named “sky-pointing.”) Red-footed boobies are usually easy to spot because they build their nests in small trees and even on top of shrubs They stick primarily to the islands of Genovesa and San Cristobal, and they’re most visible between January and September when they’re nesting.

Galapagos Penguin

Unlike its more well-known Antarctic cousins, the Galapagos penguin lives entirely in the tropics and is one of the smallest penguins in the world. It eats mostly cold-water fish, mates for life, and lives in lava caves on the islands! As an endangered species, though, the penguins are severely threatened by climate change, and currently only 2,000 of them exist in the Galapagos. They live primarily on the islands of Isabela, Fernandina, Floreana, and Santiago; visitors can also swim with them on tiny Bartolome Island off the coast of Santiago, which I did on my Galapagos cruise. They are permanent residents of the Galapagos, so you’ll be able to see them at any time of year, though they’re most visible in the cold-water months.

Waved Albatross

Named for the pattern on their wings, which looks like a wave, the waved albatross has the largest wingspan of all the birds in the Galapagos, stretching up to 8 feet long. Like the blue-footed booby, waved albatrosses participate in unique courtship routines which include circling, waddling, clacking bills, and even making a funny noise which sounds like a cow’s moo; then, they mate for life. They stick mostly to Española, and are visible from April to December during their breeding season. Unfortunately, plastic pollution in the oceans and long-line fishing, among other causes, have rendered the waved albatross a critically endangered species. Unfortunately, I didn’t see many on my visit to Española.

Flightless Cormorant

The flightless cormorant is called “flightless” because its wings are too small to support it in the air; however, those wings do help with stability in jumping along coastal rocks. This bird hunts eels and octopus on the bottom of the ocean, which it has to dive to reach. Mating between flightless cormorants involves an elaborate courtship ritual in which two cormorants intertwine their necks and move in a circle. The birds are visible on the islands of Isabela and Fernandina all year long, though nesting takes place between May and October. While not officially endangered, the Galapagos flightless cormorant species is still vulnerable to forces of pollution, climate disasters, and human influence.

Frigatebird

The frigatebird is distinguishable by its bright red throat pouch, which inflates during breeding season in order to attract a mate. Frigatebirds are colloquially called “pirate birds,” because they go to great lengths to steal food from other species. They can spend days at a time in the air thanks to their huge wingspans, but their feathers aren’t water-adapted like those of the cormorant and other birds. Frigatebirds are visible all year long, primarily on the islands of Floreana, Genovesa, North Seymour, and San Cristobal.

American Flamingo

The pinkness of the American flamingo depends on how much carotenoid it consumes through foods like crustaceans and algae. When it goes looking for those foods, it will first drag its feet through the water to stir up the sediment, then stick its head in upside down — it’s pretty funny to watch! During mating season, flamingoes engage in a unique courtship ritual by dancing in pairs of two in a synchronized pattern. Interestingly, when chicks are born, they are raised by their mothers for about three weeks before they join a large group of other new chicks, guarded by only a few adult flamingoes. (It’s like a flamingo day care!) The flamingoes in the Galapagos stick primarily to Floreana, Santa Cruz, Isabela, and Santiago, and can be seen nesting from March to July.

Finch

Made famous by Charles Darwin’s research, there are 13 different species of finch on the Galapagos Islands. Each type of finch has a unique beak size and shape which allows it to eat specific foods and live in a unique environment. Some, for example, eat seeds with the help of their short beaks, while others go after insects with their longer, curved beaks. Different finches live on different islands, but no matter which island you visit, you’re bound to see some, as they’re visible all year long. They’re more abundant in the hotter, buggier months. Bonus points because they’re so cute!

Vermilion Flycatcher

Perhaps the brightest land bird in the Galapagos, the vermilion flycatcher’s name makes a lot of sense: the males are a bright vermilion red, and their diet consists mostly of insects. During their mating season between December and May, the birds will fly straight up into the air to try to attract a mate with which they will stay for life. They build their nests high up in tall trees, and females lay three eggs per year. While birds can be found across Rabida, Fernandina, Isabela, and Santa Cruz Island, much of the forest these little guys call home has been cleared for agriculture, putting them in danger of serious population decline.

Short-Eared Owl

While most owls usually only hunt at night, the Galapagos short-eared owl is unique because it has learned to hunt in the daytime in order to eliminate confrontation with hawks. This means that you’ll have a much greater chance of seeing one than you would a regular nocturnal owl. These smart creatures have a surprising ability to hunt birds larger than themselves by sneaking up on them from behind. They live in open areas of grass or rock and nest under trees and shrubs. The owls can be spotted around the islands all year long, and a large population of them clusters on the island of Genovesa to hunt the other populations of birds there.

Galapagos Hawk

With only a few hundred birds in existence, the Galapagos hawk is probably the rarest animal on this list. In fact, it has been under Ecuadorian governmental protection since 1959! Strong beaks and sharp talons make the hawks fierce predators, but perhaps the most interesting thing about them is their system of mating. Called “cooperative polyandry,” this means that the males are monogamous, but the females are not! Then, after the eggs hatch, several males will work together to raise the newborn chicks. Nests are easy to spot, as they are usually built on the ground, in rock ledges, or in small trees. The hawks reside on Isabela and Fernandina, where they can be seen all year long.

Galapagos Land Iguana

Galapagos land iguanas are special for three reasons: first, their scales often have a beautiful golden pigmentation; second, they can live to be up to 50 years old; third, they often have adorable relationships with the islands’ finches, who like to sit on their backs. Despite the sharp claws on their toes, the iguanas don’t hunt; they eat plants instead. The female iguanas lay around 20 eggs at a time, and both she and her mate guard the nest aggressively and even violently if need be. The iguanas live on the islands of Baltra, Isabela, North Seymour, Santa Cruz, Santiago, South Plaza ,and Fernandina, and are out and about all year long.

Marine Iguana

The Galapagos’ marine iguanas are the only sea lizards on the planet! The difference between land iguanas and marine iguanas is that land iguanas prefer to hang out in solitude, while marine iguanas are typically found clumped up in large clusters, like the one pictured. Groups of the iguanas live on the islands of Fernandina, Española, Floreana, Isabela, and Santa Cruz, and each regional group turns different colors during mating season. And as if all of this isn’t interesting enough, their high-salt diet causes them to sneeze out the excess salt that their bodies don’t need! When they enter the water, their heart rate slows down to fifty percent of its normal rate so that they can spend longer periods of time feeding underwater. Could these guys get any crazier? While their mating season takes place from January to March, they can be seen sunbathing all year long.

Lava Lizard

Lava lizards, which look like tiny iguanas, can be found hanging out in the sun in large groups, sometimes with marine iguanas. They’re the most abundant reptile in the Galapagos and live on every island except Darwin, Wolf, and Genovesa. These little guys have character, too: male lizards do “push ups” to intimidate rival males, and if the opponent isn’t intimidated, he’ll join in and a push-up contest will ensue! You’ll be able to see these funny little lizards all year round.

Galapagos Giant Tortoise

These guys are a big deal in the Galapagos! In fact, the word “galápago” is an old Spanish word meaning “tortoise” or “saddle” (in honor of one of the types of tortoise). The tortoises can have two kinds of shells: domed and saddlebacked. The dome-shelled tortoises eat mostly ground vegetation, while the saddleback-shelled tortoises eat taller-growing plants. Galapagos tortoises are lazy and spend the majority of the day lounging around, and you’ll often see finches sitting on their backs. The craziest thing about the tortoises is that they can live for a year with no food or water! They’re visible on the islands of Isabela, Santa Cruz, Pinzon, Española, Santiago, and San Cristobal all year long. Today, there are ten specific types of the tortoise on the islands, but the Galapagos giant tortoise as a species is endangered.

Green Sea Turtle

The Galapagos green sea turtle lives in the subtropical waters around the islands. Females can be found laying their eggs onshore any of the islands between December and March each year. The temperature at which the eggs are incubated determines the gender of the sea turtle hatchlings, with warmer temperatures causing the hatchlings to be female! Countless larger animals prey on the hatchlings, so it is a race for the baby turtles to make it to the ocean unharmed. Once there, though, it isn’t always smooth sailing: sea turtles have been significantly affected by plastic pollution in the oceans, as they often ingest it or become entangled in it. This poses a serious threat to the species, which has been declared endangered in recent years.

Seahorse

A population of seahorses lives off the coast of Isabela and is often visible to divers and snorkelers, particularly at Las Tuneles. These tiny creatures feed on small ocean organisms like plankton, and the seahorses in the Galapagos are often yellow in pigmentation due to the specific diet available there. They are slow swimmers, which is great news for people who want to see them in their natural habitat, as they won’t zip off when you get close! Something people often don’t know about seahorses is that the males carry the babies, not the females. A “pregnant” male can carry up to 1,000+ eggs at a time after a female lays them in his pouch.

Sally Lightfoot Crab

The bright red and blue Sally Lightfoot crab was supposedly named after a Caribbean dancer for its agility and quickness — it can run in four directions! The adult crabs prefer to hang out alone and hide in the cracks of rocks when they’re not searching for food or a mate. If you bother one, don’t be surprised if one of its legs falls off! (This is a common defense mechanism for a startled crab, and they can grow back!)

Spinner Dolphin

Spinner dolphins are named for their habit of leaping out of the water and spinning on their way back down. Though small in size, they travel in groups of hundreds, and they love to show off to and interact with people. Scientists speculate on a number of reasons for the spinning: perhaps it’s to impress females during mating season, maybe it’s to assert dominance with other males, and it could be to communicate with the rest of the pod. Or, some think, maybe it’s just plain fun! After all, jumping ten feet out of the water and twirling around looks like a blast! Spinner dolphins pass through the Galapagos during their migration, so the best time and place to spot them is in the channel between Isabela and Fernandina Island from June to October.

Orca

Also known as killer whales, orcas are actually part of the dolphin family, not the whale family. The orca is one of the deadliest creatures in the ocean for two reasons: one, it has huge, sharp teeth; two, it is a super smart and highly social animal. Orcas often work together when they hunt, which means that they can take down even great white sharks. They travel in big groups and are very curious, both of which are good news for those who want the chance to see them! If there’s one, there’s a bunch more nearby, and they like to interact with people. Orcas don’t migrate in a fixed pattern, so they can be found anywhere there is a steady food source, which means that there are orcas present in the Galapagos all year long. They most commonly hang out in the western waters off of Isabela and Fernandina, but regardless, any whale-watching-tour guide will know where to find them!

Humpback Whale

From June to October, female humpbacks and their young calves can be spotted off the western coastlines of Isabela and Fernandina en route to the equator from the poles. Playful like orcas, they often propel themselves completely out of the water — a behavior called breaching. They are famous for their elaborate whale songs which can be heard thousands of miles away by other humpbacks. They are massive, too, growing up to 60 feet in length! Perhaps the most surprising fact about humpbacks, though, is that when they get hungry, they blow bubbles in the water to confuse and trap fish to eat.

Whale Shark

A name like this can lead to some confusion! Whale sharks are not whales, but sharks, and the largest ones in the ocean, at that. They can be three times the size of a great white and as long as a school bus! While they may seem scary, they’re not dangerous, as their tiny teeth don’t get put to use much in eating plankton. In the Galapagos, they’re typically found outside of the usual cluster of islands, far north near Wolf and Darwin Island; look for them from June to November. Unfortunately, commercial fishing has left the whale shark species endangered.

Scalloped Hammerhead Shark

Hammerhead sharks (specifically scalloped hammerheads in the Galapagos) are easily recognizable, and no other animal on earth looks quite like them! These cool creatures eat a ton of different ocean organisms, from small fish to squid and even stingrays. Hammerheads can hunt animals under the sediment of the ocean floor thanks to electroreceptors on their heads — it’s like an aquatic superpower! A female hammerhead also can birth up to 40 pups at a time. Like the whale sharks, they hang out far north near Darwin and Wolf, although you can also spot schools of them off of Española, Santa Cruz around Gordon Rocks, and off of San Cristobal’s Kicker Rock. They’re around all year long, but you’ll find the highest numbers of them at the beginning of the year. Illegal fishing has proven problematic for the hammerheads, though, because markets for shark fin soup in some places in Asia have led to the endangerment of the species.

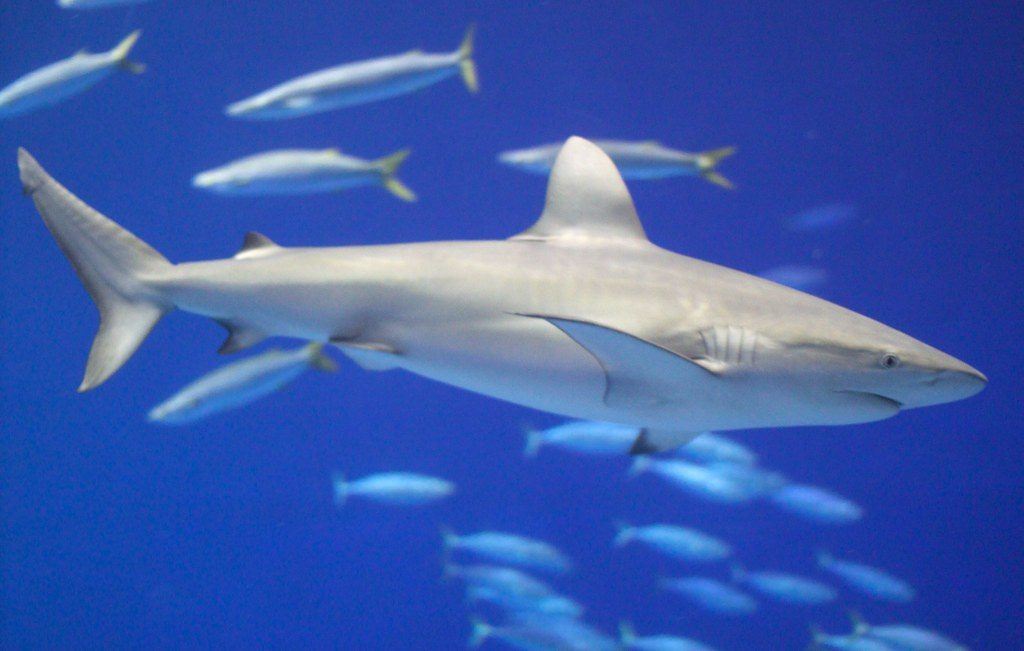

Galapagos Shark

The migratory Galapagos shark actually lives all over the world, but was first discovered and identified here in the Galapagos, so it took this location as its name. The sharks exhibit interesting behaviors around divers: when they feel threatened, they hunch up; when they get too frenzied, though, they may lurch at anything on the surface, even if it’s not something they care to eat. With 14 rows of teeth to hunt with, Galapagos sharks have practically no natural predators, so humans are the only threat to their safety and well-being. They live in the deep waters far off of Wolf & Darwin, but I’ve also seen them off of Cristobal and Española. In April, young sharks can be spotted just off the coast.

White-Tipped Reef Shark

The white-tipped reef shark is the most common species of shark in the Galapagos. It is small in size and does not behave aggressively toward humans. The sharks can be seen at a variety of ocean depths, but they usually stick to the shallows. During the daytime, they hide in caves in groups so dense that they sometimes stack on top of each other! They usually return to the same cave over and over again, too. Then at night, they come out to hunt through the coral for food. Interestingly, newborn white-tipped reef sharks are independent from the start — off on their own from day one. You can find these little guys all year long on the north half of Isabela Island and near the tiny islets of North Seymour, Champion and Gardner.

Manta Ray

The manta ray’s flat body and shape (and history of capture) gives it the name “manta,” which means “carpet”, “cloak/mantle”, and “blanket” in Spanish. Its wingspan — which isn’t wings, of course, but fins — can be more than 20 feet wide, making the mantas the largest species of rays. As filter feeders, they eat the plankton found near corals and on the surface of the water. Sometimes, manta rays propel themselves out of the water and land back on their bellies — much like breaching whales and jumping dolphins — and no one really knows why! They cluster off the northern islands of Wolf and Darwin and can sometimes be found off the southeast corner of Santiago. Look for them from December to May each year.

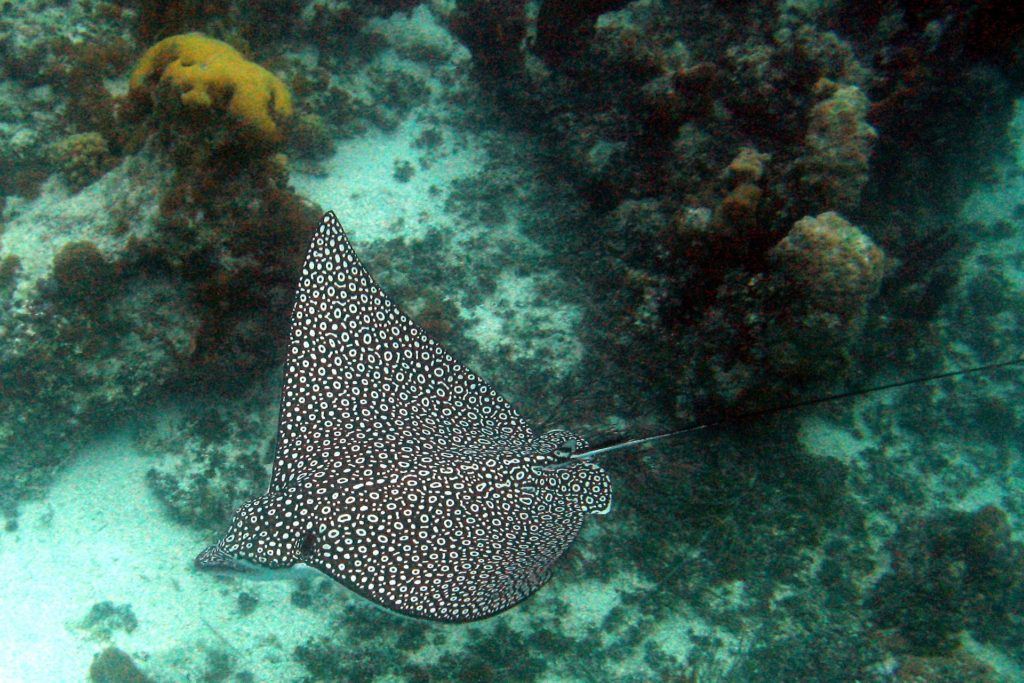

Spotted Eagle Ray

Another species of rays which calls the Galapagos Islands home is the spotted eagle ray, which is recognizable by the elaborate white pattern on its backside. The rays swim in groups and prefer to hang out in the shallow waters of bays and coral reefs. They use their strong jaws to eat crustaceans and mollusks, sometimes even stirring up the sand with their snouts in the search for food. Spotted eagle rays can also use their long tails to sting predators out of self-defense. They’re often seen doing the same leaping behaviors that the manta rays do, too! From December to May, they can be seen near the islands of Isabela, Santa Cruz, and sometimes Floreana.

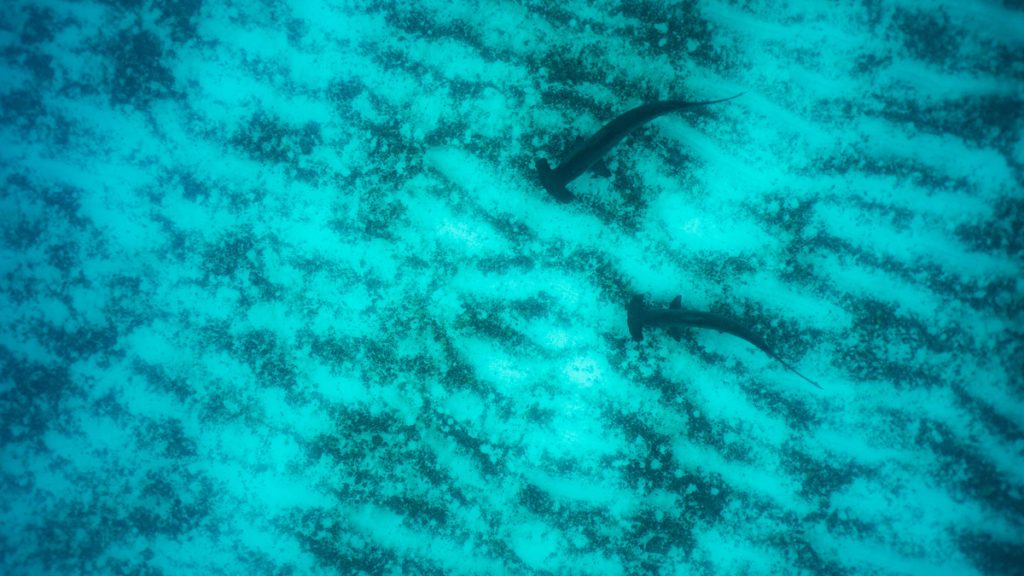

Golden Ray

Like spotted eagle rays, golden rays like to swim in groups (as depicted in the photo above), and they often hang out in lagoons. Golden rays are much smaller than manta rays at only two to three feet across. Their golden coloring helps them to camouflage into the sandy ocean floor, and sometimes they’ll bury themselves under a bit of sand to catch their prey by surprise. Like their ray counterparts, they can be seen between December and May of each year on the islands of Santa Cruz and Isabela.

Sea Lion

Sea lions are the most abundant — and the cutest — marine mammals on the Galapagos Islands. They love to lounge around on the beach, and can be seen on practically every island all year long. They can do some cool things, too: they can often “gallop” on land faster than a human can run, and they can hold their breath for up to ten minutes or more in order to dive to almost 2,000 feet below the surface of the ocean. Their mating season predominantly takes place from July to December, during and after which cute new sea lion pups can be seen all around the islands. The pups stick close to their mothers for the first year of their lives before heading off on their own. Sadly, sea lions on the Galapagos are endangered, and major climate events continually have the biggest impact on their well-being.

Though every animal of the Galapagos is amazing, it was really the sea life that had me jumping up and down, if one can do such a thing while suspended in water.

I’ll always cherish the three weeks I spent in the Galapagos islands, getting to know their famous residents and having some of my favorite animal encounters to date.

*Much of the info & some photos came from the Galapagos Conservation Trust

Tom says

What a great list of animals! The blue foot Noobie, Sally crab and that huge tortoise were my favs but that was before I made it to the end. All the Galapagos Island animals are just amazing. Don’t know orcas were frequent to the island. They are one of my favs.

Kristin says

Mine as well. I hope to swim with them one day!